Delayed word processing could predict Alzheimer’s

Research led by the University of Birmingham has discovered that a delayed neurological response to processing the written word could be an indicator that someone with mild memory problems is at an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

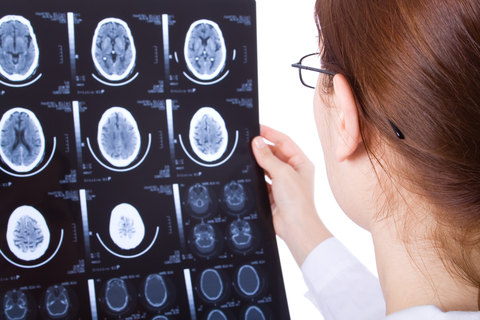

The University of Birmingham reports that, using EEG, researchers studied the brain activity of a group of twenty five people to establish how quickly they processed words shown to them on a computer screen.

The study, published in Neuroimage Clinical, was led by the University of Birmingham’s School of Psychology and Centre for Human Brain Health and was carried out in collaboration with the Universities of Kent and California.

The participants in the study were a mix of healthy older people, people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and people with MCI who had developed Alzheimer’s within three years of diagnosis of MCI.

MCI, a condition in which someone has minor problems with mental abilities such as memory beyond what would normally be expected for a healthy person of their age, is estimated to effect up to 20% of people aged over sixty five. It is not a type of dementia, but a person with MCI is more likely to go on to develop dementia.

Dr Ali Mazaheri, of the University of Birmingham, said “A prominent feature of Alzheimer’s is a progressive decline in language, however, the ability to process language in the period between the appearance of initial symptoms of Alzheimer’s to its full development has scarcely previously been investigated. We wanted to investigate if there were anomalies in brain activity during language processing in MCI patients which could provide insight into their likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s. We focused on language functioning, since it is a crucial aspect of cognition and particularly impacted during the progressive stages of Alzheimer’s.”

Previous research has found that when a person is shown a written word, it takes 250 milliseconds for the brain to process it, activity which can be picked up on an EEG.

Dr Katrien Segaert, of the University of Birmingham, said “Crucially, what we found in our study is that this brain response is aberrant in individuals who will go on in the future to develop Alzheimer’s disease, but intact in patients who remained stable. Our findings were unexpected as language is usually affected by Alzheimer’s disease in much later stages of the onset of the disease. It is possible that this breakdown of the brain network associated with language comprehension in MCI patients could be a crucial biomarker used to identify patients likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease. We hope to now test the validity of this biomarker in large population of patients in the UK to see if it’s a specific predictor of Alzheimer’s disease, or a general marker for dementia involving the temporal lobe. The verification of this biomarker could lead the way to early pharmacological intervention and the development of a new low cost and non-invasive test using EEG as part of a routine medical evaluation when a patient first presents to their GP with concern over memory issues.”